Updated with expert comment WASHINGTON: At 10:30 pm Thursday in Hawaii – 4:30 am Friday in D.C. – the Army and Navy successfully tested their Common Hypersonic Glide Body at the famed Pacific Missile Range off Kauai, the Department of Defense announced this morning. It’s only the second successful test ever of the C-HGB, 17 months after Flight Experiment 1 in October 2017.

An earlier version, the Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW), flew successfully in 2011 but failed in 2014. AHW, in turn, evolved from a design called SWERVE developed by the Energy Department’s Sandia National Laboratory.

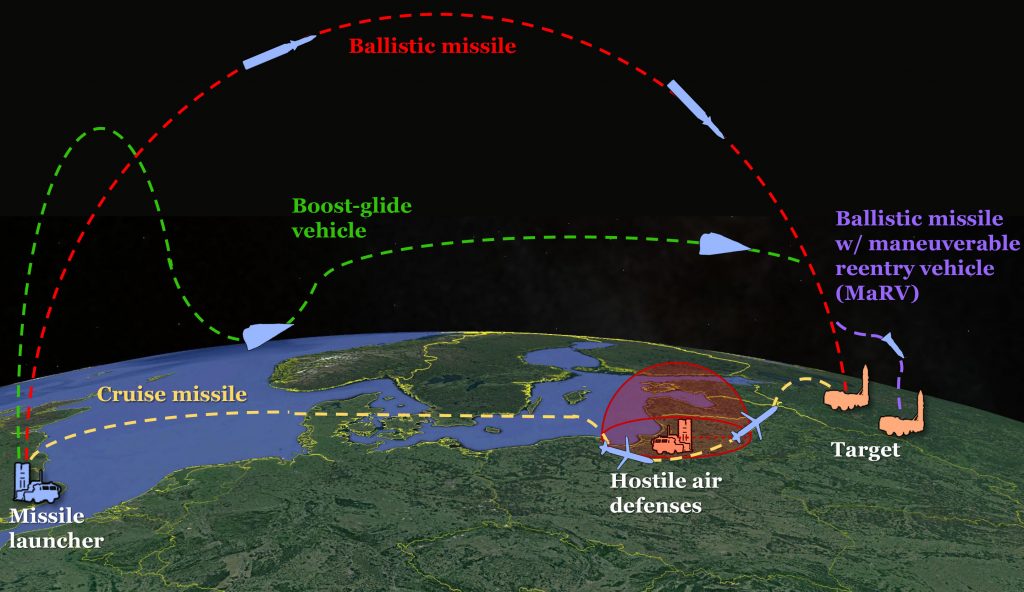

How do these weapons work? A conventional rocket booster launches the glide body, which carries the warhead, and accelerates it to hypersonic speeds – the exact figure is classified, but at least Mach 5 and possibly much more. Then the glide body separates and coasts precisely to the target, no longer able to accelerate but still able to maneuver to evade missile defenses.

Notional flight paths of hypersonic boost-glide missiles, ballistic missiles, and cruise missiles. (CSBA graphic)

While the glide body in this test was a prototype of the operational weapon, the booster rocket was not. It was “a modified Polaris A3 booster, not the common ‘stack’ that will be part of the fielded prototypes,” an Army spokesperson told me.

As Army hypersonics and lasers director Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood explained to me in a recent interview, the Army is buying the glide body for both services, while the Navy is buying the rocket booster. (The Navy’s guided missile submarines, cruisers, and destroyers give it greater experience with long-range rocketry). Each service will then customize the missile packaging for its environment, with the Army fielding a battery of four truck-borne launchers in 2023 while the Navy works on the more complex mechanics of a sea-launched version.

Since launching from aircraft is the greatest technical challenge, the Air Force and DARPA are working on two hypersonic programs of their own. One is a similar but airplane-launched boost-glide weapon called the Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW). The other, awkwardly named the Hypersonic Strike Weapon – Air Breathing (HSW-ab), is a hypersonic cruise missile that has engine power throughout its flight path.

The Pentagon was understandably sparing with details on this latest test. “The U.S. Navy and U.S. Army jointly executed the launch of a common hypersonic glide body (C-HGB), which flew at hypersonic speed to a designated impact point,” the statement says blandly.

“This test builds on the success we had with Flight Experiment 1 in October 2017, in which our C-HGB achieved sustained hypersonic glide at our target distances,” said Vice Adm. Johnny Wolfe, director of Navy’s Strategic Systems Programs, according to the statement. “In this test we put additional stresses on the system and it was able to handle them all.”

“We successfully executed a mission consistent with how we can apply this capability in the future,” Lt. Gen. Thurgood said. “The joint team did a tremendous job in executing this test, and we will continue to move aggressively to get prototypes to the field.”

“Today we validated our design and are now ready to move to the next phase towards fielding a hypersonic strike capability,” Wolfe said.

With Russia and China both touting operational hypersonic weapons — although, without a free press in either country, it’s very hard to tell how operational they really are — the Defense Department is urgently developing its own hypersonics to deter or, if necessary, defeat an adversary.

UPDATED Former Air Force missileer Brian Weeden, now at the Secure World Foundation, was skeptical about just how much progress the US hypersonics program has made. “From the statement, it appears that they have managed to improve the technology, in that they were able to do sustained hypersonic flight for longer distances, but it also seems like it’s a ways off from being an effective military weapon that is reliable enough to use in combat,” he said.

Theresa Hitchens contributed to this story.

Northrop sees F-16 IVEWS, IBCS as ‘multibillion dollar’ international sales drivers

In addition, CEO Kathy Warden says the company sees a chance to sell up to five Triton UAVs to the NATO alliance.